Pixar is one of the most successful movie studios in Hollywood. Over the years, it has collected more than 20 Academy Awards for hits like Toy Story, The Incredibles, and Finding Nemo. Its last eight films have grossed more than $500 million worldwide. The memorable characters and storylines that Pixar dreams up have delighted moviegoers of all ages.

But behind all of the box office magic is an active feedback system that’s built on candor, communication, and a surprising openness to other people’s ideas.

A complex creative process

Creating full-length animated films is definitely not child’s play. A single scene lasting just four seconds requires about 100 frames, which can take up to a week to produce. For the 2001 smash Monsters, Inc., animators spent 12 hours on each frame, many of which featured Sully, the film’s furry blue hero, and his 2,320,413 individually animated hairs, each painstakingly created to appear like the real thing.

At times, the process can seem more forensic than artistic. Story artists comb through every detail of a scene, scanning for things that probably go unnoticed by viewers – the placement of a prop, perhaps, or the way a character’s eyes roll. They do so at their own peril: Changing even one minor detail in the animation means adjusting a character’s “rig,” or the digital dimensions that shape facial expressions and body movements. Rigging is a complex web of formulas, coding, and physics, and any imprecision in the rig can compromise a character’s lifelike performance on screen.

It doesn’t end there. Further down the pipeline, bits and pieces of the story – from camera angles and lighting to sound effects and motion capture – get reviewed and revised by film editors, technical directors, and creative designers. All that trimming adds up: It took Pixar’s team five years to scope more than 146,000 images before bringing its latest hit, Inside Out, to the box office.

Making movies the Pixar way is a painstaking series of fills and cuts that lead to rapid design cycles that dunk ideas just as quickly as they’re dreamed up.

Plussing keeps the process moving

But instead of producing bottlenecks, which is what you’d expect, the process leads to breakthroughs – all because of a feedback technique Pixar calls “plussing.” Instead of shutting down ideas completely, animators try to add on to them with suggestions for improvement. So when the creative director for Pixar’s upcoming Toy Story 4 doesn’t like the way Woody’s eyes roll from frame to frame, he won’t just toss the sketch. Instead, he’ll “plus” it by asking the story artist, “I like the way you drew Woody’s eyes. What if they rolled left?”

Walt Disney is credited with developing the technique and coining the term plussing more than 60 years ago. Hear him talk about the plussing of Disneyland.

While that might seem semantic, the feedback effect is significant. Rather than reject ideas in their entirety, Pixar creates an additive approach to sharing feedback. It actively encourages artists to come up with their next steps based on the leads they receive.

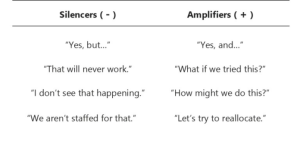

The process borrows from the tenets of improv, in which partners keep the sketch alive by “accepting all offers” and mining for comedic wrinkles in each other’s ideas. People who operate with “yes, and…” thinking use their words to amplify ideas, not silence them.

With just a simple tweak in our feedback, we help others think about ways to turn the corner rather than leaving them stranded at dead ends. And while this approach has worked wonders for Pixar, it can be applied as a non-critical feedback strategy to help just about anyone challenge their initial assumptions and come up with a better version than the one they had before.

Whether it’s big-screen success or small wins in our work or relationships, “yes, and…” thinking lets people see the world in a whole new dimension.